Mystery Officer Killed in Great War was Wordsworth’s Great-Nephew

In late October, Ingram Murray and Tom Shannon of the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum in Woodstock received good news that after years of research that took them on a journey from a garden in Northern France to across the United Kingdom, Australia, The United States of America, Ireland, Canada, and back to the battlefields of the Great War. After collaborative work with the Ministry of Defence, Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC), human remains found near Arras in the last decade were finally confirmed to be of Second Lieutenant Osmond Bartle Wordsworth, missing since 1917.

The story began in 2013 when a local farmer was digging in his private garden in the village of Hénin-sur-Cojeul discovered the remains of a body. Once the local gendarmerie had officially declared the find could not be of any criminal interest it became a case of trying to identify a missing soldier. In due course it was established that the remains were from an officer of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry based on the discovery of artefacts including a regimental button and fragments of uniform. The unknown officer was reburied ‘Known Unto God’ in 2015 with dignity and now lies with his comrades in arms. In 2016, the artefacts were transferred to the Museum so that volunteers could continue their research to try and identify the soldier.

Regimental records documented that on the 3rd May 1917, the 5th Battalion of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry attacked the enemy holding a well-established and fortified trench system in the general area. In addition to losses from artillery, the Battalion sustained heavy casualties from accurate machine gun fire and snipers, encountering an unexpected, well manned and heavily wired trench that they successfully occupied. The survivors were forced to withdraw back to their original positions after a series of strong enemy counter-attacks. 8 of the 12 officers and 291 of the 523 non-commissioned officers and men who went into action were listed as killed, wounded or missing that day, including five junior officers. Subsequent research discovered that one officer had died of wounds as a prisoner of war; a subsequent DNA comparison by JCCC was negative, and a third officer had been reported killed so would have likely been left where he fell. The volunteers concentrated on the two unresolved missing officers. Could the remains have been those of John Legge Bulmer from North Yorkshire, educated at Marlborough College before going up to Merton College, Oxford in 1913 where he knew T.S. Eliot? Could they have been of Charles Croke Harper of Broughton in Buckinghamshire who before the war was a chartered accountant and a farmer in the outback of Western Australia? Our conundrum was that although the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry were only in the area once during the Great War, the body was found approximately nine kilometres from the battlefield. In the confusion and fog of battle, was the young officer wounded and taken to a medical aid station by men of the neighbouring brigade, then buried where he died. These were questions the volunteers could not answer so had insufficient evidence to present to the JCCC to re-open the case.

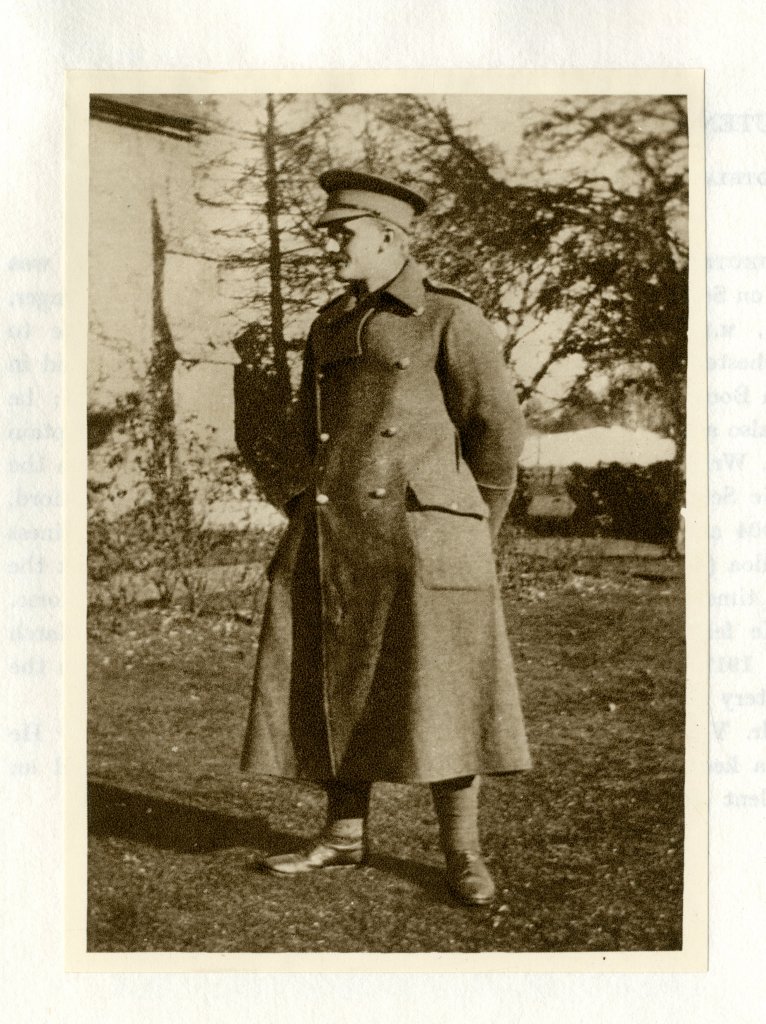

In mid-2017, one of the volunteers discovered that an officer serving in the 21st Company, Machine Gun Corps had transferred in 1916 from the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry before he was killed and buried alone by his men on the 2nd April 1917 in the village of Hénin-sur-Cojeal, one week before his division had established a formal burial location outside the village. The volunteer’s thesis was that it was possible that the young officer may have continued to wear his original Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry uniform. That officer was identified as Osmond Bartle Wordsworth, a collateral descendent of the poet. In late 2018, the Museum had the artefacts on display to assist in the search for relatives and as luck would have it a visitor advised staff that he knew a Wordsworth and contact was made with the family. Ingram presented a detailed submission to the JCCC to re-open the case with the Museum trustees, staff and volunteers rewarded for their efforts after they received the report that a DNA comparison with a relative had resulted in a match with the remains.

A re-dedication ceremony will be planned, hopefully next year, when a named gravestone will be finally placed at the head of Osmond Bartle Wordsworth’s final resting place.

Over the years, the volunteers have come to learn much about the short lives of the five missing young officers and hope that their efforts and those of the JCCC continues to honour their memory.